Definition of a “Grantor, Settlor, or Trustor” of a Trust

These terms are often interchangeable. The Grantor, Settlor, or Trustor of a trust decides how the trust will operate, including: what property to include in the trust, who the beneficiaries will be and how beneficiaries will receive their inheritance. When the trust is revocable (i.e. can be changed or terminated until the grantor dies), the grantor can change any part of the trust as often as he or she likes. When the trust is irrevocable, the Grantor typically cannot change the trust after they have signed it.

These terms are often interchangeable. The Grantor, Settlor, or Trustor of a trust decides how the trust will operate, including: what property to include in the trust, who the beneficiaries will be and how beneficiaries will receive their inheritance. When the trust is revocable (i.e. can be changed or terminated until the grantor dies), the grantor can change any part of the trust as often as he or she likes. When the trust is irrevocable, the Grantor typically cannot change the trust after they have signed it.

What is a Grantor Trust?

When a trust is classified as a Grantor Trust (from the IRS perspective) the Grantor is responsible for reporting all profits and losses generated on trust assets on their own personal tax return. Also, the assets of the trust are includable in the Grantor’s estate for estate tax purposes. (This allows a step-up in basis on appreciated assets upon the Grantor’s death.) A revocable living trust is always a grantor trust and some forms of irrevocable trusts are also considered grantor trusts.

When an Irrevocable Trust is not Considered a Grantor Trust

If the Grantor of a trust does not retain personal beneficial interest in the assets transferred to the trust, then the trust is typically not a grantor trust. This usually means that once assets are transferred to the trust, the Grantor may not receive income from the assets transferred, nor withdraw the assets for their own use or benefit.

What is an Example of a Non-Grantor Irrevocable Trust?

A typical example would be an irrevocable life insurance trust. This type of trust names a spouse, children or other people as the primary beneficiary(ies) of the trust. Assets that the Grantor transfers to the trust are considered as gifts to those beneficiaries. Those beneficiaries may have a limited right to withdraw gifts made to the trust within a short time after the assets are transferred. If they decline to do so, the trust will typically distribute those assets after the death of the grantor. In the insurance trust concept, the grantor will contribute an annual gift to the trust in order to fund the premiums on life insurance. The purpose of the life insurance is often to pay anticipated estate taxes with discounted dollars. Another purpose may be to provide a much greater financial legacy to family members in the form of tax free death benefits. At the time each gift is made to the trust, the beneficiaries are given a short window to withdraw their share of that gift, such as 30 to 60 days. If they choose to “take the cash,” then there will not be enough funds available to pay the insurance premium and the policy will lapse, leaving no residual benefit. So the question often is: Do I take the money earmarked to pay a premium of say $10,000 now? If I did I would forego a death benefit of, let’s say $500,000, after the death of the grantor. In most cases, if the beneficiaries are that short sighted, the grantor will discontinue making gifts in future years. This means that the beneficiary in question might have received only $10,000 up front, but lost the opportunity to receive $500,000 later.

What is an example of an Irrevocable Grantor Trust?

An irrevocable trust that is considered a grantor trust could be something like an Intentionally Defective Grantor Trust. The term “Defective” does not mean the trust is broken or ineffective. It means that certain aspects of the trust allow the Grantor to exercise certain rights that would not be available to them in a Non-Grantor Irrevocable Trust, such as an Irrevocable Life Insurance Trust. Such rights may include: the right to change beneficiaries, the right to have access to income from the trust, the right to replace trust assets with other assets, the right to make the Grantor individually responsible for maintenance of trust assets or for the tax consequences associated with gains and losses pertaining to the trust assets. This type of trust may also require that the assets of the trust be includable in the estate of the Grantor, upon his or her death, for estate tax purposes.

Can a Grantor be the Trustee of a Trust?

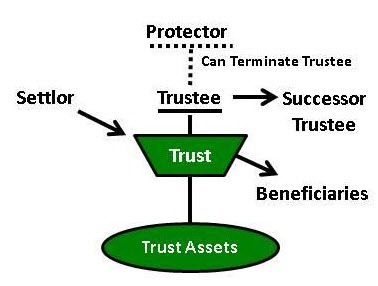

With a revocable trust, the grantor does typically act as the initial trustee of the trust. The grantor may also elect to add one or more co-trustees to act with them, or they may elect to name someone else as trustee to manage the trust for them.

With some irrevocable trusts, the Grantor may also serve as Trustee of the trust. In situations where the Grantor is giving away all beneficial interest in the assets that he or she transfers to the trust, the Grantor may not serve as Trustee of the trust.

Can a Grantor of a Trust also be a Beneficiary?

In nearly all revocable living trusts, the Grantor of the trust is also the primary beneficiary of the trust. Children or other named successor beneficiaries only benefit from trust assets after the death of the Grantor.

In fact, in the context of a revocable living trust, the person establishing a trust is usually the Grantor, the Initial Trustee, and the primary Beneficiary of the trust all at the same time. As Grantor you establish the rules for management of assets during your lifetime and the distribution of your assets after you die. You also retain the ability to make changes to anything about the trust. Then, you transfer specific assets of yours to the trust and since they are your assets to begin with, you usually appoint yourself to act as trustee to manage and make decisions regarding your assets. Once again, since you have transferred your own assets to your trust, it is logical that you would use those assets for your own benefit while you are alive, making you the primary beneficiary. Then, it is not until you become incapacitated or die that a new trustee (your specified Successor Trustee) steps into the management role over trust assets. After you die, you are no longer able to benefit personally from your trust assets, so your children or other named successor beneficiaries become the people entitled to the beneficial interest in your trust.

Can a Trust be a Member of an LLC or a Shareholder of a Closely Held Corporation?

A trust can typically be a member of an LLC. In the context of the LLC, a “member” is an equity owner of the company (LLC). If your company was formed as a Corporation, your trust can be listed as the “Shareholder” instead of you personally. There may be variations on this if your company is a Professional Corporation (where ownership and operation may depend on a professional license such as doctor, lawyer, CPA, etc).

The idea is this — in a corporation or LLC, it is the shareholders or members who elect the officers or managers to run the company. It is also the shareholders or members who are entitled to distributions of profits that the company may earn and choose to distribute. If you are individually listed as the owner and President or Manager, that means that you, as owner, elected yourself to act as the President or Manager of the company. Now if you die, you cannot vote to appoint a new President or Manager to run things. Also, you can't receive profits from the company if you are deceased.

Normally, what would happen then is Probate. The courts end up deciding who will operate your company during the probate process and the court will also decide whether your company is liquidated, sold, or if a family member will be allowed to continue to operate the company. This process can take many months or even years. By then, the company could implode or cease to be able to function as usual.

If, instead, you make your trust the Shareholder or Member, if you should die, your successor trustee can immediately step in to elect a new President or Manager (including themselves if appropriate) and continue your company without interruption. And since your trust is the shareholder or member, profits can still be distributed directly to your trust, which in turn, can be further distributed to your beneficiaries. No probate. No delays. No loss of customers, vendors, lenders or business partners.

Copyright: AmeriEstate Legal Plan, Inc.